PLA (polylactic acid) is a plant-based, compostable bioplastic made from fermented sugars such as corn, sugarcane or cassava. It offers good clarity, stiffness and food-contact safety, making it popular for cold cups, clamshells, films and 3D-printing filaments. Under industrial composting conditions, PLA can break down into CO₂, water and biomass, helping reduce reliance on fossil-based plastics. However, it has limited heat resistance, needs dedicated composting or recycling infrastructure, and must be matched carefully with each market’s 2025–2026 plastic-ban and EPR regulations.

Global concern about plastic pollution and carbon emissions has transformed packaging from a procurement line item into a strategic sustainability lever. Brand owners, retailers and foodservice operators are under pressure to phase out traditional fossil-based plastics, comply with new regulations and still protect product quality and margins. In this context, PLA (polylactic acid) has emerged as one of the most commercially mature bioplastics for packaging and disposable foodservice items.

This article explains PLA from both a scientific and practical perspective: what it is at the molecular level, how it is produced from plant-based feedstocks, where it performs well, where it struggles, and how evolving 2025–2026 plastic regulations are shaping its future. The goal is to help packaging buyers, sustainability managers and business leaders decide when PLA makes sense—and how to integrate it into a broader low-carbon, circular packaging strategy.

PLA = Polylactic Acid: Chemistry & Production

What Exactly Is PLA?

PLA (polylactic acid or polylactide) is a thermoplastic polyester. Chemically, it is a polymer built from repeating units of lactic acid, an organic acid that can be produced by fermenting sugars. Depending on how the polymer chains are arranged (stereochemistry and crystallinity), PLA can behave as a clear, glassy plastic or as a more crystalline, semi-opaque material suitable for higher-performance applications.

In industry you will see several related terms:

- PLA / polylactic acid – generic name for the polymer family.

- PLLA / PDLA – left- and right-handed stereoisomers (poly-L-lactide and poly-D-lactide) that can be blended to tune crystallinity and heat resistance.

- PLA blends – PLA combined with other biopolymers, fillers or additives to improve toughness, barrier performance or heat stability.

Biobased Feedstocks: From Plants to Polymer

Unlike conventional plastics derived from crude oil or natural gas, PLA is produced from renewable biomass. Typical feedstocks include:

- Corn starch and dextrose – the most widely used commercial feedstock today.

- Sugarcane and sugar beet – sucrose-rich crops that can also be fermented to lactic acid.

- Cassava and other root crops – regionally important starch sources in Asia and Latin America.

- Agricultural by-products and residues – a growing R&D focus: converting crop residues, bagasse, husks and stalks into fermentable sugars to reduce competition with food and feed crops.

From a climate and ESG perspective, this biobased origin means the carbon in PLA comes from CO₂ recently captured by plants, not from fossil reserves. When combined with renewable energy and efficient agriculture, this can significantly reduce cradle-to-gate greenhouse gas footprints compared with many petroleum-based plastics.

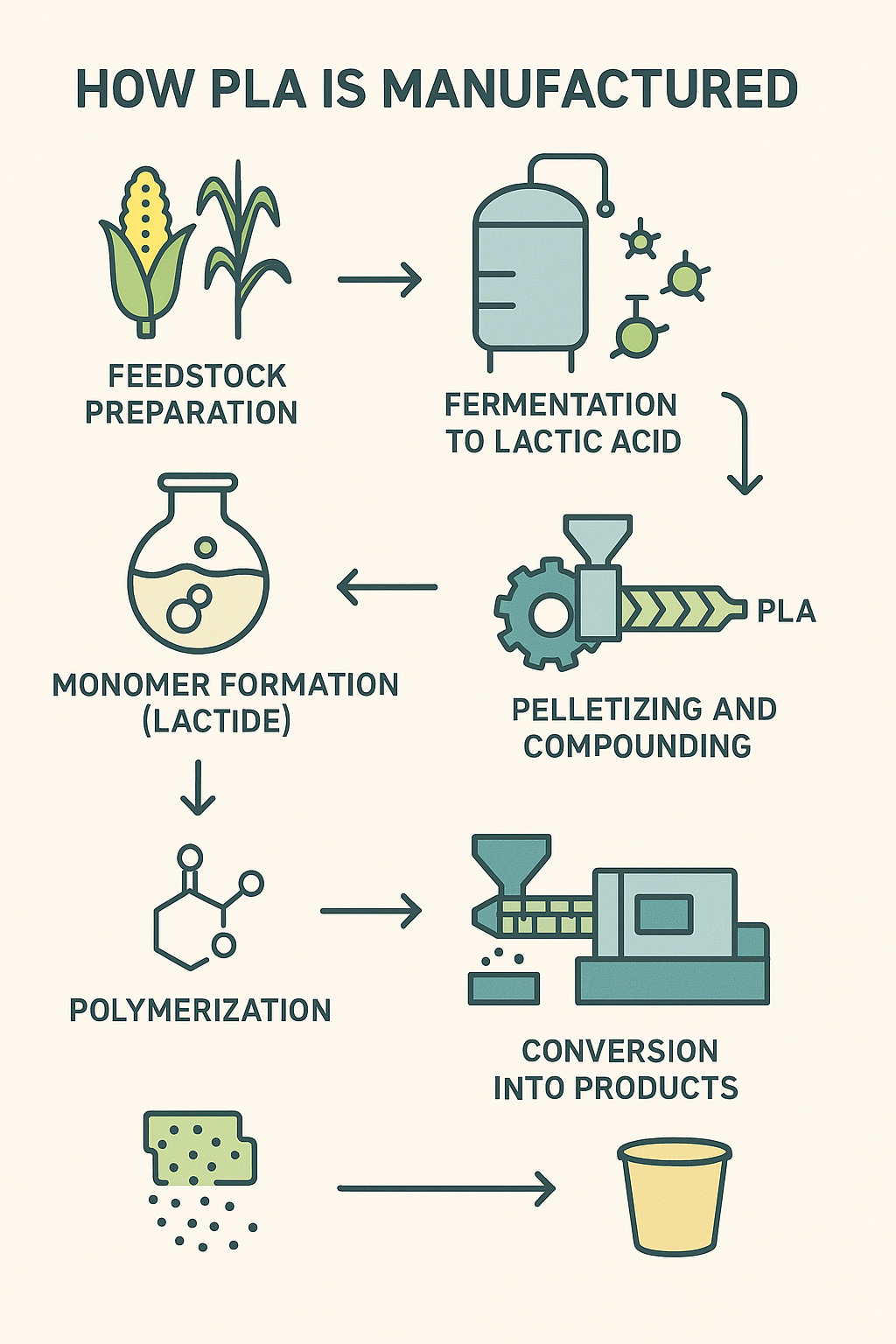

How PLA Is Manufactured

Industrial production of PLA follows a relatively well-established sequence:

- Feedstock preparation: Starch or sugar feedstocks (e.g., corn dextrose, cane sugar) are purified to provide fermentable carbohydrates.

- Fermentation to lactic acid: Microorganisms convert these sugars into lactic acid in large fermenters, similar to processes used in food and pharmaceutical industries.

- Monomer formation (lactide): Lactic acid is dehydrated and converted into a cyclic dimer called lactide, which can be purified to control stereochemistry.

- Polymerization: Through ring-opening polymerization of lactide—or, in some cases, direct condensation—long PLA chains are formed.

- Pelletizing and compounding: The PLA polymer is extruded into pellets, optionally blended with additives or other biopolymers to achieve specific properties.

- Conversion into products: Pellets are processed into finished items via injection molding, extrusion, thermoforming, film casting, blow molding or 3D-printing filament production.

This compatibility with existing plastics processing technologies is one reason PLA has scaled faster than many other bioplastics: converters can often adapt established equipment with modest changes to temperatures and processing windows.

Key Material Properties: What Engineers Need to Know

From a design and engineering perspective, several properties of PLA are particularly important:

- Thermal behavior: Standard PLA has a glass transition temperature (Tg) in the range of about 55–65 °C, above which it becomes rubbery and begins to soften. Its melting temperature typically falls between 150–180 °C depending on grade and crystallinity. Heat-resistant PLA formulations, especially those using stereocomplexing of PLLA and PDLA, can withstand significantly higher temperatures under controlled conditions.

- Mechanical profile: PLA is relatively stiff with a modulus comparable to polystyrene or PET. It offers good dimensional stability and attractive clarity for many packaging applications, but standard grades are relatively brittle with low elongation at break, which limits use in high-impact or high-flex applications.

- Barrier and optical properties: PLA typically provides good clarity and gloss, making it attractive for display packaging and cups. Its oxygen barrier performance can be adequate for some food applications, but water-vapor barrier properties are moderate, so it is often combined with coatings or multilayer structures.

These fundamentals explain why PLA excels in certain niches—such as cold cups and clamshells—while requiring modification or alternatives for hot-fill, heavy-duty or long-life packaging.

Why PLA Is Considered Sustainable — Environmental & Circular Economy Perspective

Biobased Carbon and Climate Benefits

Because PLA is derived from plants, its carbon originates from atmospheric CO₂ captured during photosynthesis. When responsibly managed, this biobased origin can reduce net greenhouse gas emissions compared with fossil-based plastics. Life-cycle assessments generally show that PLA has a lower cradle-to-gate carbon footprint than PET or PS for comparable applications, especially when renewable energy and efficient agriculture are used.

In parallel, global demand for bioplastics is expanding rapidly. Between 2024 and 2030, market analyses project double-digit compound annual growth rates, with bioplastics volumes expected to more than double and PLA remaining one of the leading product families within this portfolio. This growth is driven by regulatory pressure, corporate net-zero targets and consumer expectations for visibly “greener” packaging.

Industrial Compostability Under EN13432 and ASTM D6400

One of PLA’s most distinctive features is its industrial compostability. Under controlled conditions defined by standards such as EN 13432 (Europe) and ASTM D6400 (United States), PLA articles can be broken down by microorganisms into CO₂, water and biomass within a defined time frame, typically reaching 90% biodegradation within about 90 days in industrial composting systems.

However, this performance is achieved only when certain conditions are met:

- Sustained temperatures around 55–60 °C in the composting pile or reactor.

- Controlled moisture and aeration to support microbial activity.

- Appropriate particle size and mixing with organic waste.

In home compost, cool soil, marine environments or landfills, PLA degrades far more slowly. For sustainability managers, it is therefore crucial to align PLA packaging with robust collection and industrial composting infrastructure rather than assume “it will simply disappear in nature”.

Biocompatibility and Food-Contact Safety

PLA is generally recognized as biocompatible and has been widely investigated for medical applications such as resorbable sutures and implants, where it slowly breaks down into lactic acid—an existing metabolite in the human body. This history supports its use as a safe material for direct food contact when produced and formulated in compliance with food-contact regulations.

For food and beverage brands, PLA’s safety profile offers a compelling narrative: a packaging material originating from plants, used safely in sensitive biomedical applications, and certified to compostability standards when properly processed at end-of-life.

Supporting Circular Economy Strategies

PLA can support several circular economy pathways:

- Organic recycling (composting): When used in foodservice applications that generate mixed food and packaging waste, PLA items can be co-collected and composted together in facilities that accept certified compostables, turning residual materials into soil amendments.

- Material recycling: Dedicated PLA recycling, including mechanical and chemical routes, is technically feasible and already demonstrated at pilot and regional scales. Chemical depolymerization, in particular, can return PLA to high-purity lactic acid for re-polymerization.

- System-level decarbonization: Because the carbon in PLA is biogenic, decarbonization strategies that combine material reduction, composting and recycling can deliver substantial emissions reductions relative to business-as-usual plastic use.

The key caveat is that these benefits are not automatic. Without proper collection, sorting and processing, PLA may end up in landfills or incineration, losing much of its potential environmental advantage. This is why regulatory design, infrastructure investment and clear communication with consumers are as important as the material itself.

Common Applications of PLA in Packaging, Consumer Goods & Beyond

Food Packaging and Single-Use Serviceware

PLA has become a mainstay of compostable foodservice packaging, especially in regions where plastic bans, plastic taxes or municipal compost programs are accelerating. Typical items include:

|  |

- Cold drink cups: Clear PLA cups for smoothies, iced coffee, juices and soft drinks, often paired with PLA or paper lids.

- Clamshell containers: Salad boxes, bakery clamshells and deli containers that benefit from transparency and stiffness.

- Portion and sauce containers: Small cups for dressings, condiments and tasting samples.

- Cutlery and straws: In some markets, PLA or CPLA (crystallized PLA) cutlery and straws are used as alternatives to PS or PP items.

These products are especially attractive for quick-service restaurants, cafés, juice bars and institutional catering that want to align with sustainability goals, communicate a plant-based story to customers and comply with restrictions on conventional single-use plastics.

PLA Cups and “Compostable Plastic Cups”

Among all PLA applications, clear PLA beverage cups are one of the most visible to consumers. They bridge three priorities that matter in foodservice:

- Brand and product visibility: Transparency, gloss and printability make PLA cups a strong medium for logos and graphics while showcasing the drink itself.

- Operational compatibility: PLA cups run on existing cup-filling and sealing lines with minor process adjustments and can be stacked, transported and used much like conventional PET cups—within their temperature limits.

- Regulatory positioning: Certified compostable PLA cups can help operators transition away from banned or taxed plastics under regulations inspired by the EU Single-Use Plastics Directive and similar national policies.

However, heat sensitivity is non-negotiable. Standard PLA cups are best kept below about 45–50 °C and are not suitable for hot coffee or tea. Businesses frequently pair PLA cold cups with paper-based hot cups to cover all beverage use cases without compromising safety.

Films, Bags and Flexible Packaging

PLA can also be extruded into thin films for flexible packaging:

- Fresh produce and salad bags where clarity and compostability are valued.

- Flow-wrap for bakery items, snacks or bars when shelf life requirements are moderate.

- Labels and sleeves for bottles and containers.

In many cases, PLA films are combined with other biopolymers or specialty coatings to improve toughness, sealability or barrier properties. For organic waste collection, PLA and other compostable films are increasingly used for certified compostable bin liners that can be processed in industrial composting facilities.

3D Printing, Consumer Goods and Medical Uses

Outside packaging, PLA is arguably the default material for consumer 3D printing. Its relatively low processing temperature, dimensional stability and low emissions make it ideal for desktop FDM printers in schools, design studios and maker spaces. It allows rapid prototyping of components and visual models without the odour or VOC profile of some petrochemical plastics.

In the biomedical sector, purified and specially formulated PLA and its copolymers have long been used in absorbable sutures, implants and drug-delivery systems. These applications reinforce PLA’s image as a biocompatible material and demonstrate its ability to break down into metabolizable lactic acid within the body under controlled conditions.

PLA vs Traditional Plastics & Other Bioplastics — Advantages and Limits

Key Advantages of PLA

Relative to conventional plastics like PS, PET and sometimes PP, PLA offers several strategic advantages:

- Renewable, biobased origin: PLA’s carbon originates from plants, supporting corporate targets for biobased content and reduced reliance on fossil feedstocks.

- Industrial compostability: Certified PLA products can be accepted in industrial composting systems that handle food and organic waste, enabling organic recycling pathways where infrastructure exists.

- Food-contact safety and positive perception: Regulatory approvals for food contact and associations with medical applications support a “safe and clean” narrative that resonates with consumers.

- Processing familiarity: PLA can be processed on existing plastics equipment with moderate adjustments, allowing converters and brand owners to scale without completely redesigning their factories.

- Regulatory fit: In markets implementing bans on certain fossil-based single-use plastics, compostable PLA items can be positioned as compliant alternatives (subject to local definitions and labeling rules).

Material Limitations and Performance Gaps

Despite these strengths, PLA is not a universal replacement for all plastics:

- Limited heat resistance: Its relatively low Tg means standard PLA will soften and deform around 55–60 °C. This rules out applications involving hot-fill, oven use, long microwave cycles or exposure to very hot environments (e.g., car dashboards in summer).

- Brittleness: Without modification, PLA tends to be brittle with low impact resistance, making it unsuitable for products that require repeated flexing, strong hinge performance or high impact toughness.

- Moisture and barrier constraints: While acceptable for many food applications, PLA’s water-vapor barrier and long-term mechanical stability in humid conditions may be insufficient without coatings or multilayer designs.

Comparing PLA to Other Bioplastics

Within the wider bioplastics family, PLA sits alongside materials such as PHA, starch blends, PBS and biobased versions of conventional plastics (e.g., bio-PET).

- Versus PHA: Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) can offer superior biodegradability in marine and soil environments and better performance in some flexible applications. However, PHA is currently more expensive and less widely available than PLA.

- Versus starch blends: Starch-based materials may compost readily but can suffer from poorer mechanical properties and moisture sensitivity. PLA often provides better strength and processability.

- Versus bio-PET or bio-PE: These biobased drop-in plastics can be fully compatible with existing recycling streams but are not inherently compostable. PLA, in contrast, prioritizes compostability and biobased origin over full compatibility with fossil-plastic recycling systems.

For decision makers, the comparison is less about “PLA versus everything else” and more about aligning each material’s strengths with specific use cases, regulatory context and available end-of-life pathways.

Systems Challenges: Infrastructure, Labelling and Consumer Behaviour

Many of PLA’s perceived weaknesses are actually system design issues:

- Infrastructure gap: Industrial composting facilities and dedicated PLA recycling streams are not yet universal. Without them, compostable items may still go to landfill or incineration.

- Contamination concerns: If PLA enters conventional plastics recycling streams in significant quantities, it can contaminate PET recycling unless properly sorted.

- Labelling confusion: Consumers often conflate “biobased”, “biodegradable” and “compostable”. Clear, honest labelling and education are essential to avoid greenwashing and mis-disposal.

These challenges are being addressed through updated standards, clearer legislation and harmonized labeling requirements in many regions—but the transition is still in progress.

The Future of PLA — Innovations, Industry Trends & What to Watch

Material Innovation: Tougher, Hotter, Smarter PLA

R&D in PLA and PLA-based blends is moving quickly. Key directions include:

- Improved heat resistance: Stereocomplex PLA (combining PLLA and PDLA) and specialized nucleating agents can significantly increase heat deflection temperatures, enabling PLA to withstand higher service temperatures in certain applications.

- Enhanced toughness: PLA blended with impact modifiers, elastomers or reinforcing fibers can improve impact resistance while maintaining compostability when carefully formulated.

- Better barrier properties: Nanocomposites and multilayer structures are being explored to improve oxygen and moisture barriers for more demanding food and beverage applications.

These advances are gradually expanding the envelope of where PLA can perform, especially in hot-fill, takeaway and reusable-type designs where today’s standard grades fall short.

Next-Generation Feedstocks and Land-Use Considerations

To address concerns about competition with food crops and land use, the PLA industry is increasingly investigating:

- Agricultural residues: Straw, husks, bagasse and other lignocellulosic residues as sources of fermentable sugars.

- Non-food crops: Dedicated non-food biomass grown on marginal lands, reducing pressure on prime farmland.

- Integration with bio-refineries: Using shared infrastructure where sugars, bioplastics, biofuels and biochemicals are co-produced, improving overall resource efficiency.

From an ESG reporting perspective, the ability to document lower land-use impact and reduced indirect emissions will become a differentiator among PLA suppliers.

Recycling and Chemical Depolymerization

Beyond composting, chemical recycling—particularly depolymerization back to lactic acid—is one of the most promising developments for PLA. In principle, this allows:

- High-purity monomer recovery from mixed or contaminated PLA streams.

- Closed-loop production of new PLA without loss of performance.

- Integration with broader recycling systems where composting is limited.

Several companies and research groups have demonstrated technology pathways for PLA depolymerization at pilot scale. As policy moves to recognize chemical recycling routes and as PLA volumes grow, these technologies may become integral to regional circular-economy strategies.

Regulation, EPR and 2025–2026 Plastic-Ban Timelines

Tightening regulation is perhaps the most powerful driver of PLA adoption. Inspired by the European Union’s Single-Use Plastics Directive and similar national laws, many jurisdictions are:

- Banning or restricting specific fossil-based single-use plastic items such as cutlery, plates and straws.

- Introducing Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes that make producers financially responsible for packaging waste.

- Implementing plastic taxes and minimum recycled-content rules for conventional plastics.

Between 2025 and 2026, more regions are moving from voluntary commitments to binding restrictions, creating strong incentives to adopt certified compostable or recyclable alternatives. PLA will not be the only winner in this transition, but its maturity, commercial availability and established standards position it as a central pillar in many companies’ sustainable packaging roadmaps.

Summary & Recommendations — When PLA Makes Sense for Sustainable Packaging

Recap: What PLA Does Well

Used in the right context, PLA offers a compelling combination of benefits:

- Biobased origin and potential for reduced carbon footprint versus many fossil plastics.

- Industrial compostability under recognized standards when processed in suitable facilities.

- Good clarity, stiffness and food-contact performance for cold and ambient applications.

- Compatibility with existing plastics processing technologies and equipment.

- Alignment with 2025–2026 plastic reduction, EPR and sustainability regulations in many markets.

Where PLA Is a Strong Strategic Fit

PLA is particularly well suited for:

- Cold beverage packaging: Smoothie, juice and iced coffee cups, especially where composting or organic waste collection exists.

- Fresh food and salad packaging: Clamshells, deli containers and salad bowls that benefit from transparency and short to medium shelf life.

- Foodservice and catering: Takeaway containers, lids, portion cups and cutlery in venues where compostable items can be collected with food scraps.

- Brand storytelling: Applications where a visible shift to plant-based, compostable materials reinforces sustainability positioning and ESG commitments.

When to Be Cautious or Combine PLA with Other Solutions

PLA is not ideal for:

- High-temperature use: Hot-fill beverages, ovenable trays or long microwave heating cycles.

- Heavy-duty, long-life items: Products requiring repeated mechanical stress or long service lives under variable environmental conditions.

- Regions without composting or dedicated recycling routes: Markets where all packaging ultimately goes to landfill or basic incineration, with no credible pathway for compostable materials.

In these cases, companies should consider a portfolio approach: combining PLA with other bioplastics, fiber-based materials, and improved recycling systems rather than expecting one material to solve every issue.

Action Points for Procurement and Sustainability Teams

For organizations evaluating PLA today, practical next steps include:

- Mapping current and future regulatory requirements in each target market (including definitions of “compostable” and labeling rules).

- Assessing the availability of industrial composting or PLA recycling partners in key regions.

- Selecting PLA grades and product designs that match real-world use temperatures, mechanical stresses and logistics conditions.

- Designing clear on-pack communication and signage to guide customers on correct disposal and manage expectations about what “compostable” means.

- Integrating PLA into a broader climate and circularity roadmap that includes material reduction, reuse models and conventional recycling where appropriate.

Read correctly, PLA is not a silver bullet—but it is a powerful tool in the toolkit for companies facing accelerating plastic bans, EPR fees and stakeholder pressure to decarbonize packaging between now and 2030.

PLA FAQ: Top Questions from Google Search

1. Is PLA really biodegradable?

Yes—but with important conditions. PLA is biodegradable and compostable under controlled industrial composting conditions defined by standards such as EN 13432 and ASTM D6400. In these facilities, with sustained temperatures around 55–60 °C, oxygen and moisture control, PLA can break down into CO₂, water and biomass within a few months. In home compost, soil, rivers or oceans, degradation is much slower and may not meet practical timescales, so disposal pathways matter as much as the material itself.

2. Can PLA go into normal plastic recycling bins?

In most regions today, the answer is no. PLA has different melting and processing characteristics than PET or HDPE, so if it enters conventional plastic recycling streams in large quantities, it can contaminate the recycled resin. Some municipalities and private programs are beginning to pilot dedicated compostable or PLA-specific collection, but as of 2025–2026, these systems are still emerging. Always follow local guidance: in some markets, certified compostable items are sent to organic waste collection rather than plastics recycling.

3. Is PLA safe for food and beverages?

When produced by reputable manufacturers and used within its intended temperature range, PLA is considered safe for food-contact applications. It is widely used for cold beverage cups, salad boxes, clamshells and other packaging that directly touches food. Safety depends on compliance with relevant regulations (e.g., EU, FDA or other national food-contact requirements), quality control during production and appropriate use (for example, avoiding exposure to temperatures above its recommended limits).

4. Can PLA cups be used for hot drinks?

Standard PLA cups are not suitable for hot beverages such as freshly brewed coffee or tea. Because PLA begins to soften near 55–60 °C, hot liquids can deform the cup, compromise structural integrity and create a poor user experience. For hot drinks, brands typically rely on paper cups with suitable linings, fiber-based solutions or high-heat bioplastics and compostable coatings specifically engineered for elevated temperatures.

5. How does PLA compare to paper packaging in terms of sustainability?

PLA and paper are complementary rather than competing materials. PLA offers clarity and plastic-like performance for cold cups, clamshells and films, while paper and molded fiber excel in opaque containers, trays, bowls and lids. From a sustainability standpoint, both can be sourced from renewable resources, and both can participate in circular systems: PLA via composting or chemical recycling, paper via recycling and composting. The best solution usually combines fiber-based structures with biobased coatings or compostable plastics, optimized for local infrastructure and regulatory requirements.

Semantic Insight Block: How to Use PLA Strategically in a Plastic-Ban World

How should businesses think about PLA in 2025–2026? Treat PLA not as a one-size-fits-all “eco plastic” but as a strategic material for specific use cases where its strengths—biobased origin, clarity, stiffness and industrial compostability—directly align with business goals and available infrastructure. For many food and beverage brands, that means prioritizing cold cups, salad clamshells and foodservice items that travel with organic waste into composting systems.

Why is regulatory context so important? The same PLA cup can be a sustainability asset in a city with industrial composting and clear labeling, or a missed opportunity in a market where all waste goes to landfill. With plastic bans, EPR fees and packaging directives tightening between 2025 and 2030, procurement decisions should be made country by country, factoring in local rules on compostables, labeling and collection.

What portfolio of options should a packaging team consider? A resilient strategy rarely relies on just one material. Leading brands combine PLA with fiber-based packaging, recycled-content plastics, reusable formats and system-level interventions such as deposit schemes. PLA is strongest where it reduces fossil plastic use, simplifies sorting (e.g., “all items in this venue are compostable”) and supports clear communication to consumers.

Which options emerge as the most future-proof? Solutions that link material choice to verifiable end-of-life outcomes—certified composting, traceable recycling, real waste-diversion data—are likely to outperform purely symbolic changes. PLA will remain a key part of this mix when paired with robust certification (EN 13432 / ASTM D6400 or equivalent), credible infrastructure partners and transparent reporting on environmental performance.

What should decision makers watch over the next 3–5 years? Three developments deserve close attention: expansion of industrial composting and organic waste collection; commercialization of PLA chemical recycling at scale; and new generation PLA grades based on agricultural residues with improved heat resistance and toughness. Together, these trends will determine how far PLA can move from “niche eco alternative” to a core pillar of mainstream sustainable packaging systems worldwide.

References

European Bioplastics Association – “Bioplastics Market Data and Global Capacity Outlook” – European Bioplastics

US Department of Agriculture (USDA) – “Bio-based Materials: Production and Market Trends in North America”

European Commission (EU Single-Use Plastics Directive) – “Guidance on the Scope and Implementation of SUPD Measures” – European Commission Environment Directorate

NatureWorks LLC – “Lifecycle Assessment of PLA Production from Corn-Based Feedstocks” – NatureWorks Technical Brief

Journal of Polymers and the Environment – “Thermal and Mechanical Behavior of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Under Industrial Conditions” – Springer Science+Business Media

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) – “Global Assessment of Single-Use Plastics and Policy Pathways”

International Solid Waste Association (ISWA) – “Compostability Standards and Organic Recycling Infrastructure in OECD Countries”

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) – “ASTM D6400 Standard Specification for Labeling of Plastics Designed to be Aerobically Composted”

European Committee for Standardization (CEN) – “EN 13432: Requirements for Packaging Recoverable Through Composting and Biodegradation”

Journal of Renewable Materials – “Advances in Feedstock Diversification for PLA: Agricultural Residues and Non-food Biomass” – Tech Science Press